On Mexican Consciousness: Part I: Film

|

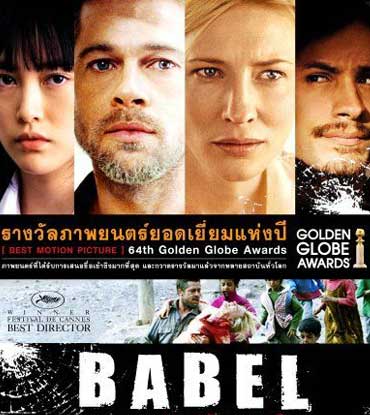

| Hey, who put me on the cover of this movie? |

It is very difficult for me to summarize a topic as broad as the consciousness of a people. Although I cannot properly consider myself "Mexican," there are many Latino/Hispanic people who share both my ancestry and cultural dilemma. Consider California: we have an overwhelming population of Mexican Americans here, with the most vibrant communities of recent and established generations of immigrants proud to call this country their home, yet firmly rooted in their own culture and traditions. Today I need to remember that I should be sensitive even with labels; the majority of my friends greatly prefer the term Latino even when my family has considered itself Hispanic for so long. I could write for a long while on the distinguishing characteristics of New Mexican identity, even though I have never lived in New Mexico itself. Rather I find it helpful to take the macro scale: identifying those trends in Latin American culture that unite us as a people. We are the ones who transcend labels, whose identity fuses uniquely with land and communal values. We are a meta-modern people whose presence calls structures into question. This is expressed in the great movements of Liberation Theology as well as a strong contribution to the arts. It is perhaps in the latter movement that I find myself at home and can grasp some important connections that include me in this unique experience. My first topic in this unfolding series is that great medium that speaks to so many young people like me: film.

It's no surprise that I would choose to write on this topic, considering some of my favorite films of all time are Mexican produced or helmed by Mexican artists. Before Crash introduced the American cinema to the hyperlink story, the great Alejandro González Iñárritu created such works as Amores Perros and 21 Grams, weaving seemingly unrelated, disparate story lines into a continuous, often tragic arc that may play with the rules of chronology.

I've identified a few trends that are helpful to look out for should you embrace the beauty of the Mexican contribution to film. The first, and probably most immediate for Latinos is the idea of communal storytelling. That is, the characters of these films do not create individual storylines in themselves, but rather inhabit threads of a larger tapestry that is connected to the greater, unified narrative. The Hyperlink genre is a wonderfully effective vehicle for this idea. Although I readily recommend the stories made in the Spanish language, several of the most prominent directors (the Big Three, as I call them) have crossed over into the international English language movie business. Iñárritu is one of these, making 21 Grams and Babel to illustrate two distinct mythological concepts expressed in the films' titles. In 21 Grams, the stories of three characters come together in the aftermath of a tragic car accident. Guillermo del Toro brilliantly portrays a born-again Christian who turns himself in after running over two children and their father in the street. Naomi Watts plays the grief-stricken mother determined for revenge, and Sean Penn as the guilt-addled recipient of the father's donated heart. The film is cut in a non-chronological order and may disorient upon first watch. A little easier to stomach may be his later film Babel, which replaces the localized drama of interweaving threads with a more international scale. These films illustrate the principle in that the characters are rendered meaningless outside of the larger narrative. Details become apparent as the other characters begin filling them in. Without the collective consciousness, the film falls apart. It is this fragility, often underscored by the tragic circumstances of the films (none of my recommendations are for children) that make them so affecting. Latin American identity is marked by its fragility. What is rooted in the pride of Spanish ancestry often obscures the suffering and shame associated with indigenous heritage. And yet, they are part of the same fabric; they cannot be dissociated from each other.

I've identified a few trends that are helpful to look out for should you embrace the beauty of the Mexican contribution to film. The first, and probably most immediate for Latinos is the idea of communal storytelling. That is, the characters of these films do not create individual storylines in themselves, but rather inhabit threads of a larger tapestry that is connected to the greater, unified narrative. The Hyperlink genre is a wonderfully effective vehicle for this idea. Although I readily recommend the stories made in the Spanish language, several of the most prominent directors (the Big Three, as I call them) have crossed over into the international English language movie business. Iñárritu is one of these, making 21 Grams and Babel to illustrate two distinct mythological concepts expressed in the films' titles. In 21 Grams, the stories of three characters come together in the aftermath of a tragic car accident. Guillermo del Toro brilliantly portrays a born-again Christian who turns himself in after running over two children and their father in the street. Naomi Watts plays the grief-stricken mother determined for revenge, and Sean Penn as the guilt-addled recipient of the father's donated heart. The film is cut in a non-chronological order and may disorient upon first watch. A little easier to stomach may be his later film Babel, which replaces the localized drama of interweaving threads with a more international scale. These films illustrate the principle in that the characters are rendered meaningless outside of the larger narrative. Details become apparent as the other characters begin filling them in. Without the collective consciousness, the film falls apart. It is this fragility, often underscored by the tragic circumstances of the films (none of my recommendations are for children) that make them so affecting. Latin American identity is marked by its fragility. What is rooted in the pride of Spanish ancestry often obscures the suffering and shame associated with indigenous heritage. And yet, they are part of the same fabric; they cannot be dissociated from each other.  A more recent trend with Mexican cinema is its violent contrast between traditional magical realism and gritty, unflinching portrayal of the world. I just watched Guillermo del Toro's masterpiece set in postbellum Spain, El Laberinto del Fauno. Although Del Toro, as the second of the Big Three, is known more for his contributions to fantasy and sci-fi in the US (think Hellboy), he is most at home in the purely Latin genre of magical realism. As Americans we are often comforted by finding comfort in ordinary circumstances, explaining the success of shows like The Office and the self-deprecation of Louis C.K. and Jon Stewart. The Mexican lens flips this on its head by finding the ordinary in fantasy, in the fantastic, dark, and mystical. Although this genre is more generously treated in literature (we'll have to wait for a later installment for me to flesh out my commentary there), it is well represented by del Toro's refreshingly original fable of young Ofelia's journey to complete the Faun's three quests to inherit her subterranean crown. The story begins with the young girl immersed in the pages of a book, recounting the cuentos de las hadas that offer her solace from the trauma of dislocation, an oppressive household, and the aftermath of a war that took her father's life. As you watch the film, you become increasingly aware of the director's use of color to underscore the child's experiences. Each of her ventures into the realm of the faun and the fairies is painted in vivid earth tones, while the world above is bleary, gray, and blue. Del Toro puts his creatures to effective use as they convey a world that at once inspires wonder and leaves you with unease, as if the iconic Pale Man from the table will pop out from around a corner any time soon to devour you. Yes, there is violence, death, and tragedy here, but the message is one of overall hope. There is even beautiful imagery to honor the Catholicism so inherent to Mexican consciousness which you can pick out in key moments, if you know where to look.

A more recent trend with Mexican cinema is its violent contrast between traditional magical realism and gritty, unflinching portrayal of the world. I just watched Guillermo del Toro's masterpiece set in postbellum Spain, El Laberinto del Fauno. Although Del Toro, as the second of the Big Three, is known more for his contributions to fantasy and sci-fi in the US (think Hellboy), he is most at home in the purely Latin genre of magical realism. As Americans we are often comforted by finding comfort in ordinary circumstances, explaining the success of shows like The Office and the self-deprecation of Louis C.K. and Jon Stewart. The Mexican lens flips this on its head by finding the ordinary in fantasy, in the fantastic, dark, and mystical. Although this genre is more generously treated in literature (we'll have to wait for a later installment for me to flesh out my commentary there), it is well represented by del Toro's refreshingly original fable of young Ofelia's journey to complete the Faun's three quests to inherit her subterranean crown. The story begins with the young girl immersed in the pages of a book, recounting the cuentos de las hadas that offer her solace from the trauma of dislocation, an oppressive household, and the aftermath of a war that took her father's life. As you watch the film, you become increasingly aware of the director's use of color to underscore the child's experiences. Each of her ventures into the realm of the faun and the fairies is painted in vivid earth tones, while the world above is bleary, gray, and blue. Del Toro puts his creatures to effective use as they convey a world that at once inspires wonder and leaves you with unease, as if the iconic Pale Man from the table will pop out from around a corner any time soon to devour you. Yes, there is violence, death, and tragedy here, but the message is one of overall hope. There is even beautiful imagery to honor the Catholicism so inherent to Mexican consciousness which you can pick out in key moments, if you know where to look.For as indebted as the Mexican psyche is to fantasy and mythology, it draws increasingly from avant garde filmmaking cinema verite, a French genre that we all can recognize whenever we see a shaky, handheld camera at work. Although virtually commonplace now in the director's toolbox, some of the best pieces of art from Mexico plunge you right into the midst of the scene and leave you breathless. I speak of none other than my favorite movie, Children of Men, which seamlessly blends the world of science fiction (it takes place in a dystopian 2027) with the grittiest of filmmaking techniques. Director Alfonso Cuarón (the final piece of our Trinity) was committed to a particular style of setup in key scenes of the film, including a heart-stopping car sequence with no cuts that puts anything in Jurassic Park to shame (unfortunately, it's been compared). The climactic scene where insurgents lay siege to a refugee camp was filmed in one take, and stuns with every re-watch. Look no further than the spatters of dust and blood which cover the camera lens at follows the protagonist Theo on his quest to reluctantly shepherd humanity's last hope (notice a trend here?) I recommend this film to be viewed several times over, since it gives nothing away by means of explanation (all key plot points are revealed through incidental dialogue, newspaper clippings, or implied references).

Cuarón is to thank for his masterful work on the third installment of the Harry Potter franchise. Sure, his Dementors will leave us without sleep for nights, but the overall mood showcase his immense creativity and imagination that suit the fantasy genre perfectly. I love Children of Men for its profoundly emotional and spiritual overtones, but from a purely aesthetic perspective, it shines among the finest films of the past fifteen years.

The final attribute of the Mexican film can be expressed most soberly through its treatment of the recent violence in the drug war. Although its music and literary figures predicate a more obvious form of melodrama, film offers a more nuanced medium to convey its lingering concern with tragedy. We can return to Iñárritu to offer us the most fully flawed, tormented, and irrational characters. As surely as we can rely on Britain to offer us asexual, cool-headed rationalism (think Sherlock), we are sure to depend on the Mexican's full perspective on lament. The 2009 immigration-themed drama Sin Nombre simultaneously traces the journey of poor Guatemalan migrants travelling the train tracks to reach the fabled Norte while escaping vicious Honduran and Salvadoran gangs, notably La Mara, known to Californians by their Orange County based branch, MS-13. Their tactics put the Blood and Crips to shame, where eight year old children fashion handmade pistols to execute rival bosses encroaching on neighborhood turf. All this is treated without omission in the story that leaves you wondering if a Mexican knows what a happy ending is. For a Brazilian take on the scene, try the acclaimed and breathtaking City of God. As one director put it, to tell the story of the drug war with a tinge of hope betrays the deaths of so many at the hands of their merciless killers. They must be honored with honesty. We are not afraid of lament, ironically enough, considering the suicidal sense of machisimo that drives much of the bloodshed on screen and in real life.

The final attribute of the Mexican film can be expressed most soberly through its treatment of the recent violence in the drug war. Although its music and literary figures predicate a more obvious form of melodrama, film offers a more nuanced medium to convey its lingering concern with tragedy. We can return to Iñárritu to offer us the most fully flawed, tormented, and irrational characters. As surely as we can rely on Britain to offer us asexual, cool-headed rationalism (think Sherlock), we are sure to depend on the Mexican's full perspective on lament. The 2009 immigration-themed drama Sin Nombre simultaneously traces the journey of poor Guatemalan migrants travelling the train tracks to reach the fabled Norte while escaping vicious Honduran and Salvadoran gangs, notably La Mara, known to Californians by their Orange County based branch, MS-13. Their tactics put the Blood and Crips to shame, where eight year old children fashion handmade pistols to execute rival bosses encroaching on neighborhood turf. All this is treated without omission in the story that leaves you wondering if a Mexican knows what a happy ending is. For a Brazilian take on the scene, try the acclaimed and breathtaking City of God. As one director put it, to tell the story of the drug war with a tinge of hope betrays the deaths of so many at the hands of their merciless killers. They must be honored with honesty. We are not afraid of lament, ironically enough, considering the suicidal sense of machisimo that drives much of the bloodshed on screen and in real life.Yes, there are many lighthearted adventures to be had with the Mexican cinema (check out the romp Rudo y Cursi, or the underrated American takes on its cinema, Casa de Mi Padre). I paint with broad strokes because these films and their creators have affected me in such powerful ways. If you think I've painted a picture of a Mexico that is overly concerned with is stereotypes of violence and drug addiction, then you miss the point. It is a culture of artists, willing to embrace the ambiguity and dirt as real as the earth in El Valle de México and transform it into something meaningful, something intrinsically worthwhile, something sacramental. Perhaps this will ignite a desire for you to delve more deeply into your heritage through its contribution to art. I know I am proud to consider myself a part of the larger story that finds its way onto the screens of admirers the world over.

Thorough and entertaining take on Mexican cinema! I especially enjoyed your mention of Jurassic park, lib Theo, and our metamodern culture. Curious to hear how you think Mexican embrace of pain (i.e lament) in cinema can help others embrace their own lament. In other words, how can Mexican cinema positively impact U.S. culture?

ReplyDeleteGreat question, Nomes; I didn't have the chance to treat the subject in this round, although I'm sure I'll write on it in further explorations of Mexican art. As you can see, I'm fairly long-winded. Though I don't believe art always needs to be moralized (think "Piss Christ" for a photographic analogue), I do think you're onto something when it comes to the perspective on pain. The most instructive aspect to our American culture has to do with embracing the gap in experience caused by normative experiences of suffering. Mexico is not unique in its ability to infuse meaning into suffering and captivate our sterile lives, especially since even our standards of poverty still accommodate relative luxuries like flatscreen TVs and video games. This all amounts to our own culture's particular ability to distract itself, and Mexico (although a middle income country) continues to struggle with vast disparities that cannot be ignored. Thus, in providing sometimes shocking insensitivity to this pain, we are compelled to experience what most in our world live with daily. Still, I respect the Mexican artist's right to portray violence and suffering even without an inherent moral dimension, since it seems to me (and my main point in the post above will demonstrate) that the primary concern of such artists is catharsis rather than warning.

ReplyDelete