A Manifesto on Belief

|

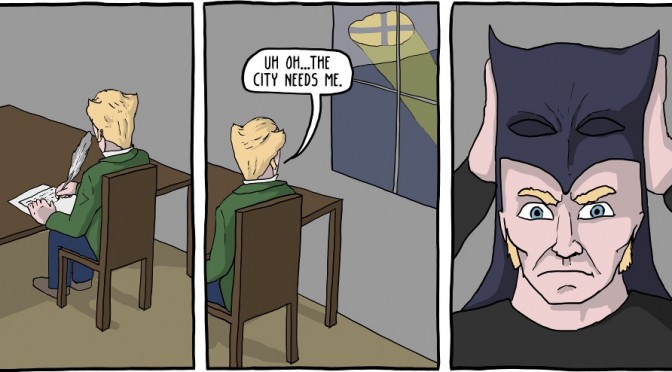

| He's not the Existentialist we deserve... |

A Manifesto on Belief

I've thought about a helpful proposition to summarize the wisdom of the late-modern and postmodern thinkers. It follows:

- Humankind is subject to inescapable suffering, which deprives it of objective meaning.

- Human attempts to remedy suffering inevitably devolve into sectarian tribalism and competition for resources.

- Ultimately, humankind's existential condition cannot be changed, because it has only so much control over its circumstances as creatures.

- There is no evidence for any "supernatural" being, and the vast majority of God-talk upholds superstition at its most harmless best, and unspeakable atrocity at its brutal worst.

- Humankind will only be free when liberated of belief: ideology and God are dictators when considered as objective. "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God."

- In choosing action, to lay down one's life for the sake of mercy, humanity will encounter truth in the subjective experience of it all: pain and joy, sorrow and prosperity. "Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the land."

- Humankind's liberation from belief and our participation in life's depth invites it to truly address the needs and suffering of its members, motivated not by the reward of "heaven," but by the richness of renewed relationships and experience. "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled."

- With sober eyes squared directly at its suffering and joy alike, humanity is free to truly live, and thus encounter meaning without having to construct it in dogma. "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of heaven."

- Thus the fullest example of a life lived fully in this encounter, paradoxically speaking of the divine and the evanescent, is finally found in Jesus of Nazareth, whose revelation as the Christ provides a universal and accessible invitation into the fullness of life's depth. "I am the way, the truth, and the life."

These reflections are my best attempt to get at the ideas that were presented in the depths of the Second World War by the German Confessing pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and their implications upon the church at large. The choice of a "confessional" format mimicking the faith expressions of many denominations, church bodies, and congregations around the world is explicitly ironic. In point 5, this "confession" says that humanity's freedom is contingent on the rejection of belief, ideology, God. Albert Camus interprets Kierkegaard's liberative "leap of faith" in the converse, that it is in leaping away from heaven that is the more difficult path, not in the intellectual desert of belief as the Danish philosopher saw. Bonhoeffer wrote in the depths of a Nazi prison cell, months away from his eventual execution, that "before God and with God we live without God." To be sure, this type of religionless Christianity was taken up by a variety of theological streams and developed decades after his death. I want to argue that this radical concept of denial and negation is the truest expression of faith and spirituality that we in the West have, stripped of our modernist sensibilities and reasonable intellection. Because of the influence of capitalist-consumer-driven society, we have replaced any real spiritual sensitivity with a cloying tendency to self-gratify, and thus most of our worship services look and feel more like rock concerts (and not very good ones, I have to say) that eschew the difficult questions in lieu of packaged, doctrinal answers. This tendency towards systematization and dogmatic declarations runs through all institutional religion, and thus proved the major stumbling block for Jesus himself (who was executed by the state for a largely religious crime, at the behest of his Jewish contemporaries), the Buddha (whose own followers disobeyed his wishes that his teachings would not become institutionalized) and the Sufi mystics (who became martyrs for their poetic and nondual interpretations of Koranic wisdom).

So how to implement such a Manifesto? Am I arguing, in these lines, to forsake our ties to organized religion and life as "spiritual revolutionaries," eager to topple the idols we see infused in our culture for greedy consumption? Should we stop attending church, and cease instructing our children in morality based on the traditions handed down to us? Can our lives never be free of such pain? Yes and No.

The simple reality is that, no matter what privilege we hold, no matter our abilities to reason, philosophize, or sermonize on life's meaning, we all face the final threshold of existence: that is to say, it is finite. We are all going to die. This is unavoidable, and ultimately the majority of "heaven-talk" does little but distract us from attending to our present. Kierkegaard thus sought a reasonable approach to this perspective's remedy by placing the "perfect" transcendence of God just beyond our ability to apprehend. Instead of submitting our will to the "leap of faith" entailed by the Great Dane, we are allowed, if we heed Camus and Sartre (I know, the former hates being lumped in with the latter) we can experience the truth and breadth of life within our very experience. Thus, attending to our freedom, true freedom from the lure of a fictional "heaven" detached from our world, we can paradoxically find the reality that Jesus himself preached: The Kingdom of Heaven is at hand!

For me, this brings a profound consolation, a salve to remedy the "mortal despair" that so anguished Kierkegaard and made his contemporaries laugh at him. For Camus, in particular, the body, simple pleasures, and even the shining of the sun become friends and rich invitations to enjoy. In the Christian tradition, we can understand this as the manifestation of God's creation, and how it bear's the "fingerprints" or "God's grandeur." It begs to be understood introspectively. "If there is a sin against this life, it consists perhaps no so much in despairing of life, as in hoping for another life and eluding the quiet grandeur of this one." Such could be uttered from the lips of the mystics, and yet we find these words spoken by a French Algerian agnostic, womanizer, and hedonist.

Do I argue for the denial of the church? It's complicated. I have many friends and family members who are far from committed Christians, and yet live moral lives affected by a genuine concern for life. I do not understand their highest freedom to be linked to a confession of faith that characterizes much of the evangelical Christianity in which I was raised. I was appalled to hear that, during a recent relative's funeral, the preacher forced the gathered mourners to raise their hands if they were "saved" or not. Any fool can raise a hand. It takes courage to endure the eyes and threat of hell leveled on otherwise reasonable people. Should this type of church be abandoned? I must answer clearly, in case you didn't guess, HELL YES. This is a parody of religion.

But all faith-systems do not function this way. In my own Catholic church, I return each week to participate in the Mass not for its ritual significance, but in its effectual reality: each week I am required to submit my intellect and will in an act of profound unity. Communion is more than a memorial, or "symbol," but a part of the reality to which we profess. "Mass," after all, means mission. And yet for many my church is not a space of safety and freedom, but rather a reminder of a sinister past, or worse. This is all acceptable, and I encourage the free person to explore which communities will further foster their freedom.

A thoughtful biblical reader will object with Jesus' own words: "The one who wishes to save their life must lose it (Matt 16:25)."Thus to take his words plainly, we do proclaim another, different life to aspire towards. True, and yet, did not the Teacher from Galilee illustrate this truth to his followers by responding to the men who wished to follow him and yet would not give up their familial and material obligations? There is a reason the Rich Young Man remains a fixture in our affluent Western imagination. Too easily dismissed as a scapegoat by religious folk, he is in fact a clear embodiment of our behavior. To deny ourselves is in fact to find ourselves, and I think that Jesus offers a beautiful opportunity to inhabit the fullness of our freedom. We serve the poor and needy, not because it will earn us the points needed to get us beyond the pearly gates, but in doing so we recover the broken threads that have unraveled in our scarcity-minded selfishness. To lay the life of slavery-to-wealth down in favor of the free live interdependent with others may cost us our lives in the end (as it did Jesus), but we do so facing the End with our conscience liberated into our only hope: that which is apprehended by our lived experience. I am a Christian not because I hope for a "better" life, but because I want to experience the fullness of the one that I have been given, and wish to throw off any illusion that I could ever have another.

Epilogue

Why did I title this treatise a "Manifesto," you ask? It may be to raise eyebrows, to point towards other helpful works that call into question the foundations of our world. It may be that I wish to honor the works of another "Karl." But no, this is not a political ideology (although these ideas have implications that are profoundly political). You may feel the need to develop or defend your own ideas on belief. I welcome your thoughts.

Comments

Post a Comment